The standard view in reinforcement learning (RL) is to treat RL policies as static functions that map states to actions. Policies typically spend a fixed amount of compute, regardless of the complexity of making the correct decision in the underlying state. For example, for a humanoid robot, the action of where to move the right foot is easy, but figuring out how to efficiently pack furniture in a truck requires more deliberation. In RL, this limitation is often solved by citing Moore's law and simply scaling the number of policy parameters. But the compute required to make good decisions in different situations can span many orders of magnitude; using a static massive policy with a large number of parameters is wasteful. Additionally, as compute becomes cheap, the complexity of the world and sensory data also increase, making it infeasible to simply scale up policy parameters.

The main contributions of our work are:

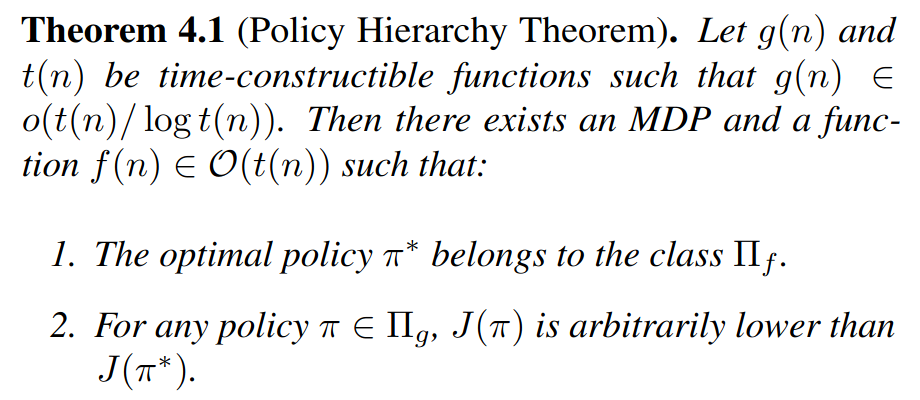

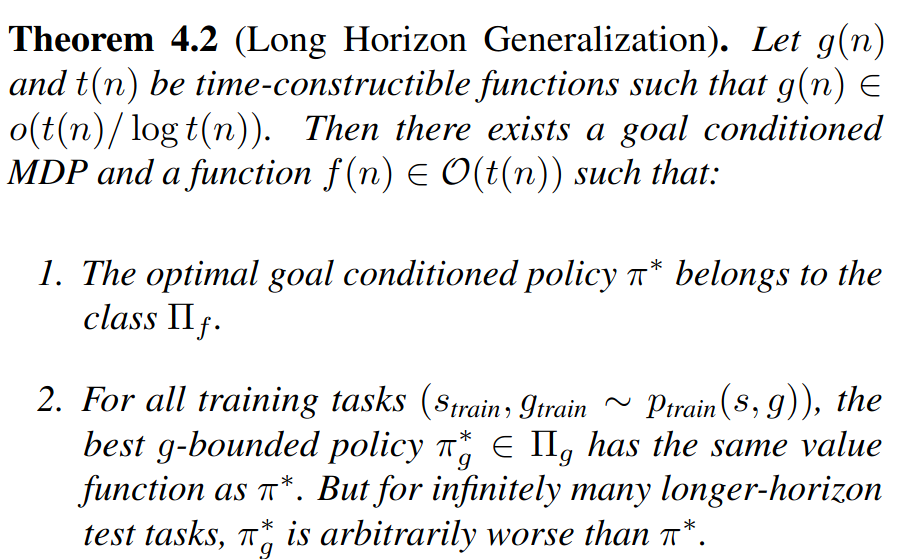

- We advocate for a computational view of RL, where computation time and parameter count are distinct axes. We formulate RL policies as bounded models of computation and prove that policies with more compute time can achieve arbitrarily better performance and generalization to longer horizon tasks depending on the MDP.

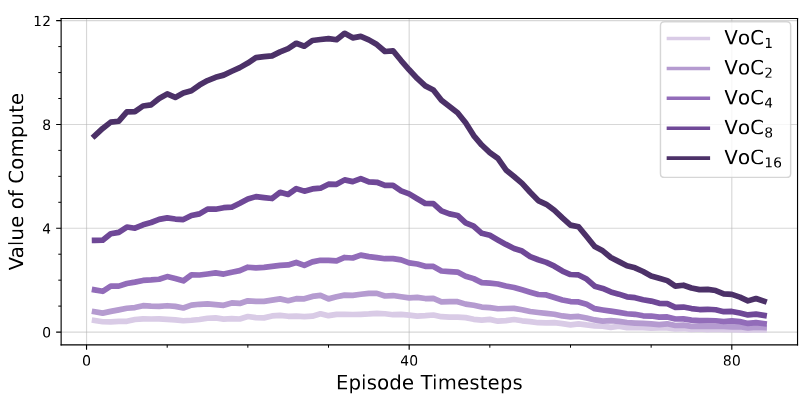

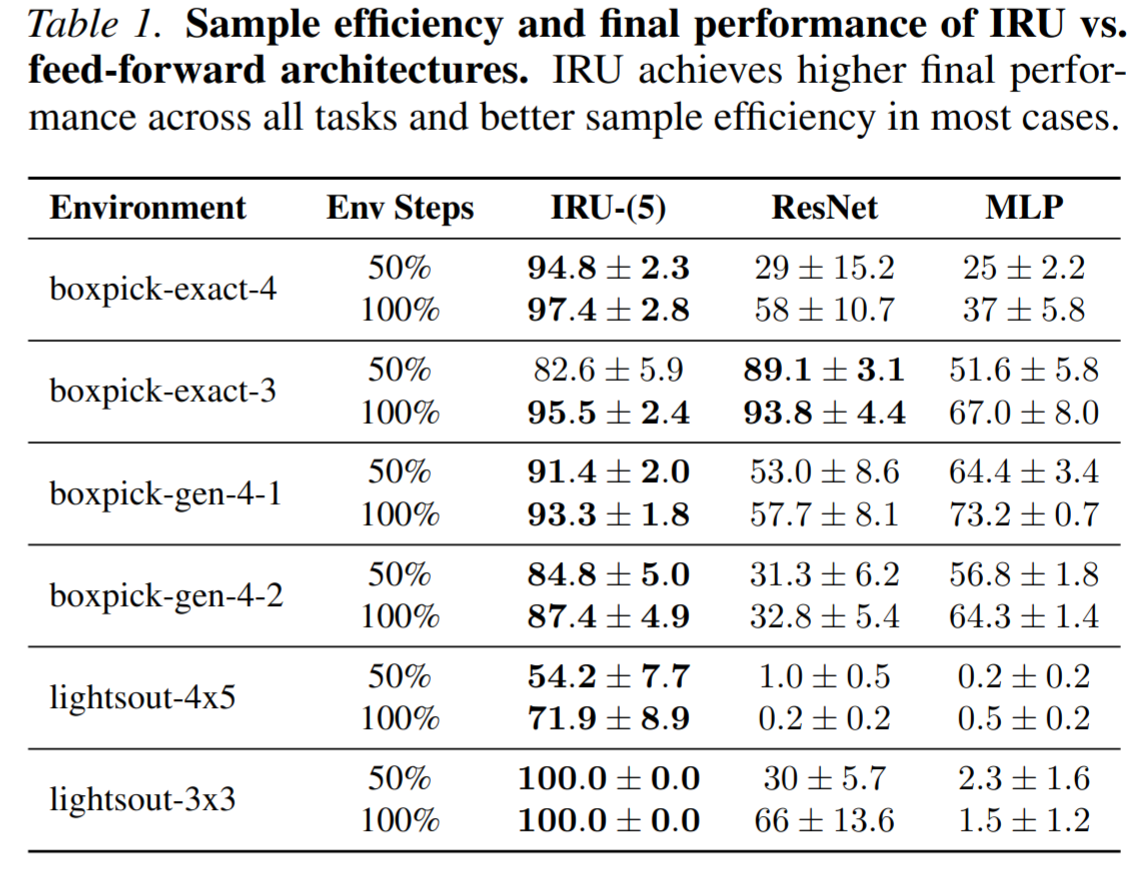

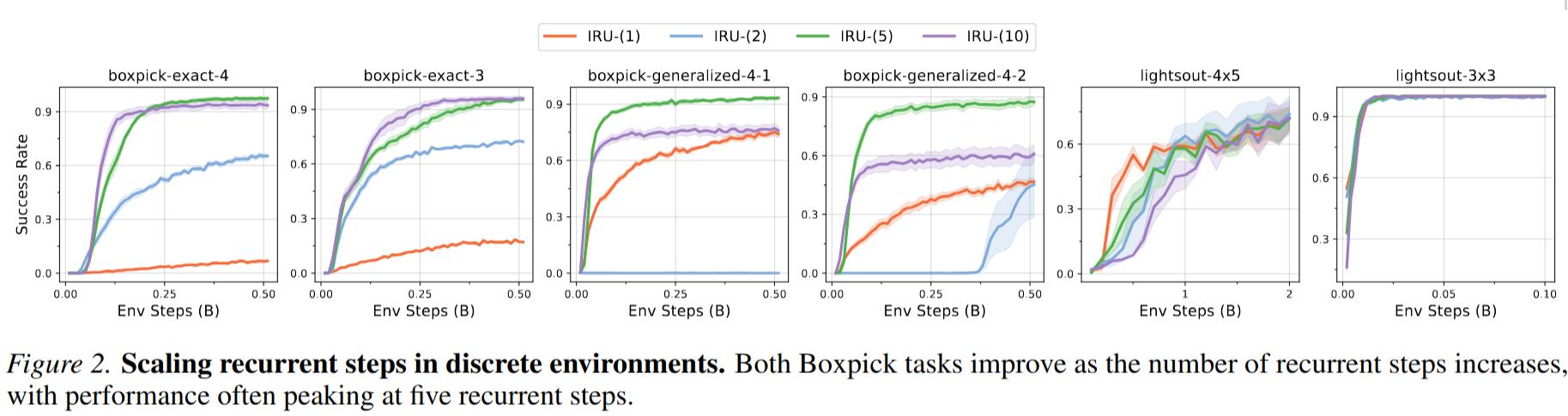

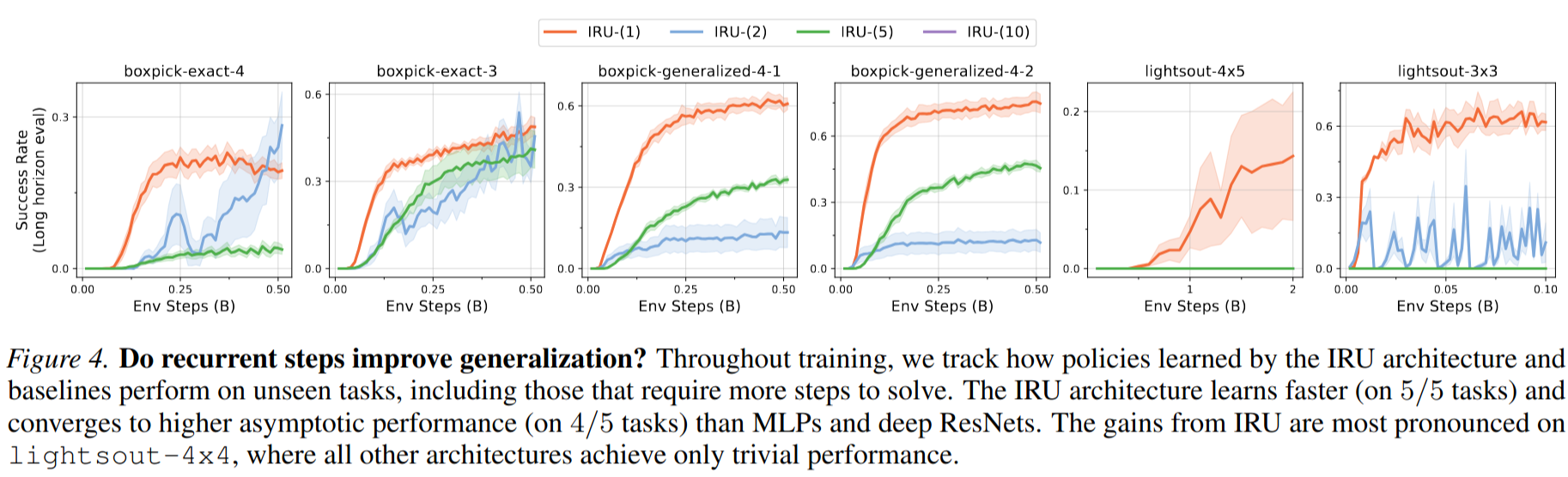

- We empirically show that RL policies which use more compute achieve stronger performance as well as stronger generalization to longer-horizon unseen tasks